This GitHub repository contains keyboard optimization algorithms based on heuristic search techniques and greedy approaches.

The algorithms have been developed using a massive corpus of STEM research papers and the optimized keyboard configurations can be tried out here.

The keyboard optimization problem is NP-complete, meaning that there is no way to verify whether any particular solution is the optimal one, unless we evaluate every possible solution.

This implies an infeasible amount of time required due to the sheer number of keyboard configurations, coupled with the massive size of the text corpus.

We instead turn to heuristics based approaches to arrive at an approximation of the optimal solution.

The arXiv Dataset is a dataset of over 2 million scholarly papers across STEM, complete with associated metadata of each paper.

Due to space constraints, I only consider the abstracts of each paper, and not the entirety of it. Furthermore, the typing patterns of each paper will more or less be captured within its abstract.

One could even argue that considering the entirety of each paper would skew the data with unnecessary field-specific jargon.

Now for the part I'm most excited to write😋, let's start with the modelling the keyboard as an object.

For the sake of simplicity, I only consider the alphabets of the keyboard as swappable, since numbers and punctuation marks scattered across the keyboard would make the layout even harder to learn than any new layout already is.

If we append the rows of the keyboard, we get a 1D array of alphabets of length 26. Every unique keyboard configuration will have a unique vector of alphabets. Hence to represent all of the unique 26! keyboard configs, a simple array of it's alphabets(rows appended) is enough.

If positions of any two keys of the keyboard are switched, it results in a different array, and hence a different keyboard configuration.

For any given keyboard config, there are 26C2=325 possible pairs of keys that can be switched, and hence 325 new keyboard configs can be reached.

If we consider each keyboard config as a node in a tree data structure, the branching factor will be 325. But, each branch of the tree is not disjoint, i.e. we can reach any key config from any other key config, making it a graph data structure.

How exactly do we determine if a key config is better or worse than another? We know that different people have different habits, speeds and proficiencies in typing. It would seem difficult to generalize an evaluation metric if typing habits of people are so diverse.

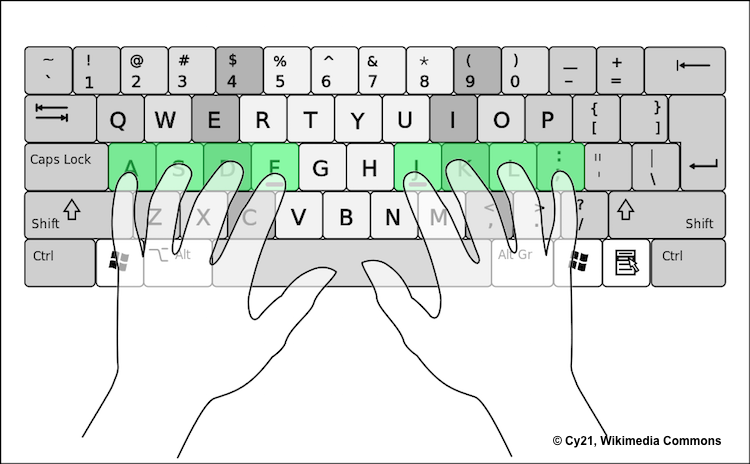

It is here that we have to make an assumption considering the most widespread method used to type: the standard QWERTY layout with default key assignments to the fingers.

The row offsets of the standard QWERTY keyboard are also fixed for consideration. To postulate our assumption in formal terms:

if two individuals use the same keyboard layout, with the same finger assignments for each key, and the same physical offsets for each row, then the total distance travelled by each of their fingers while typing the same paragraph of text is equal, regardless of individual typing speed or proficiency.

And hence it follows that minimizing the distance travelled by the fingers will result in an increase in the typing speed and efficiency of any user, regardless of proficiency.

The key length of every key is constant(19.05 mm) and the 2nd, 3rd rows are offset by 1/4th and 1/3rd of a key length respectively. Padding between keys is also constant and can be removed from distance calculations.

With the help of the above observations, we calculate the distance travelled to hit each key by the corresponding finger, and store it in an array according to key positions.

Note that the actual letter pressed does not matter, but only it's position in the key array does. For example, the distance required to hit the 5th key in the key array will not change regardless of the actual key placed in the 5th position in the key array.

- Same Key Redundancy:

- If the same key is pressed consecutively(for eg: typing the word 'steer'), the second press of the consecutive key does not require any finger traversal, since it is already on the key.

- In general, for any number of consecutive key presses of the same key, the distance travelled is equal to the key being pressed only once.

- Same Finger Penalty:

- If two distinct keys are pressed consecutively by the same finger, i.e. both keys have the same finger assignment, the finger doesn't travel from it's original resting position to the second key.

- For example, in the QWERTY layout, both letters of the word 'by' is typed by the right index finger consecutively. The index finger first travels to the bottom row to 'b', before travelling to the top row to type 'y'

- In general we can assume that typing consecutive alphabets using the same finger multiple times decreases efficiency and speed. Hence we add a fixed penalty to the loss function in addition to the distance travelled naturally.

- It is a simple, primitive approach to optimizing the keyboard config. It entails simply counting the occurrences of each alphabet in a given paragraph, and iteratively assigning the alphabet with the highest number of occurrences to the position in the keyboard which requires the minimal distance to reach.

- Count optimization significantly reduces the distance travelled by the fingers(by about almost half the initial value).

- Since this is a rudimentary approach, it does not address the nuances to the loss function.

- We define the set of all possible keyboard configs as a search space, with the initial config as the initial state.

- We use the loss function described above as a heuristic to evaluate the current state.

- We then evaluate each of the possible states of the keyboard that result from any one of the 325 transitions aplied to it.

- From the calculated losses, we find the config with the lowest loss and make that keyboard config our new current state.

- This is done iteratively until for a particular state, none of the possible states have loss lower than current loss.

- The algorithm terminates having arrived at a local minima in the state search space.

- To ensure arrival at viable solutions, we can ensure that our initial state itself is optimized to a certain degree.

- This is why Count Optimization is used in conjunction with Heuristic Optimization.

- This algorithm doubles down on the observation that: A better initial state input to the algorithm results in a better final state after execution.

- The dataset is split into batches and the output of Heuristic Optimization on a one batch is input to the next, until all batches have been processed.

- Applying Heuristics-based Optimizations in batches is a lot more feasible and runs much faster than using the entire dataset at once.

- To use these algorithms on your own dataset, ensure you have the dependencies mentioned in requirements.txt installed(use pip install -r requirements.txt).

- Make sure to take a look at the preprocessing steps in the keyboard.ipynb notebook to ensure you have the proper data format.

- Note that the algorithms utilize paralllelized processing to speed up the process by splitting the input dataframe to dask bags. Take a look at the dask documentation if you are unfamiliar with it.

- The optimization functions in optimizer.py take arguments for changing the number of partitions of the dask bag, modify it according to the size of your dataset. The default values are only recommendations.

- You can also modify the Same Finger Penalty parameter of the algorithms and experiment with different values.

- If you would like to contribute to this project, please open an issue or a pull request on the GitHub repository.